BY CAMILA ACEVEDO

This Non-Profit works tirelessly to Free Minors from Border Detention Centers and Reunite them with their loved ones

Dina Nayeri once said, “It is the obligation of every person born in a safer room to open the door when someone in danger knocks.”

Opening doors is precisely what the phenomenal volunteers and staff at Each Step Home (ESH) strive for every day.

ESH, formerly known as Every Last One, is a non-profit organization dedicated to ending the damage caused by negligent and inhumane treatment of children under U.S. immigration policy.

Although the organization caters to immigrants from a wide array of countries, most clients are from Central America, primarily Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala.

ESH’s mission is to do whatever is necessary to get children released from government custody and placed in safe, loving homes and communities.

The organization is largely run by volunteers, divided into various teams in accordance with the services they provide, offering guardians and family members help with completing arduous paperwork, connecting with immigration lawyers, and enrolling minors in school. Moreover, they offer free medical services, translation assistance, and other critical resources.

Different Treatment

In recent years, it has become evident how immigrants who travel to the United States to seek refuge have been treated and portrayed very differently depending on their home country.

A starkly apparent example is how media outlets from across the world, spanning the political spectrum, have praised the courage of Ukrainian refugees (some reporters labeling them heroes).

By contrast, these same media outlets seldom portray Latin American refugees—who have been fleeing their homelands for decades as a result of similar human rights violations—under a similar light.

Families, children, and individuals who migrate from Central America to the United States most often do so to escape horrific violence and political instability.

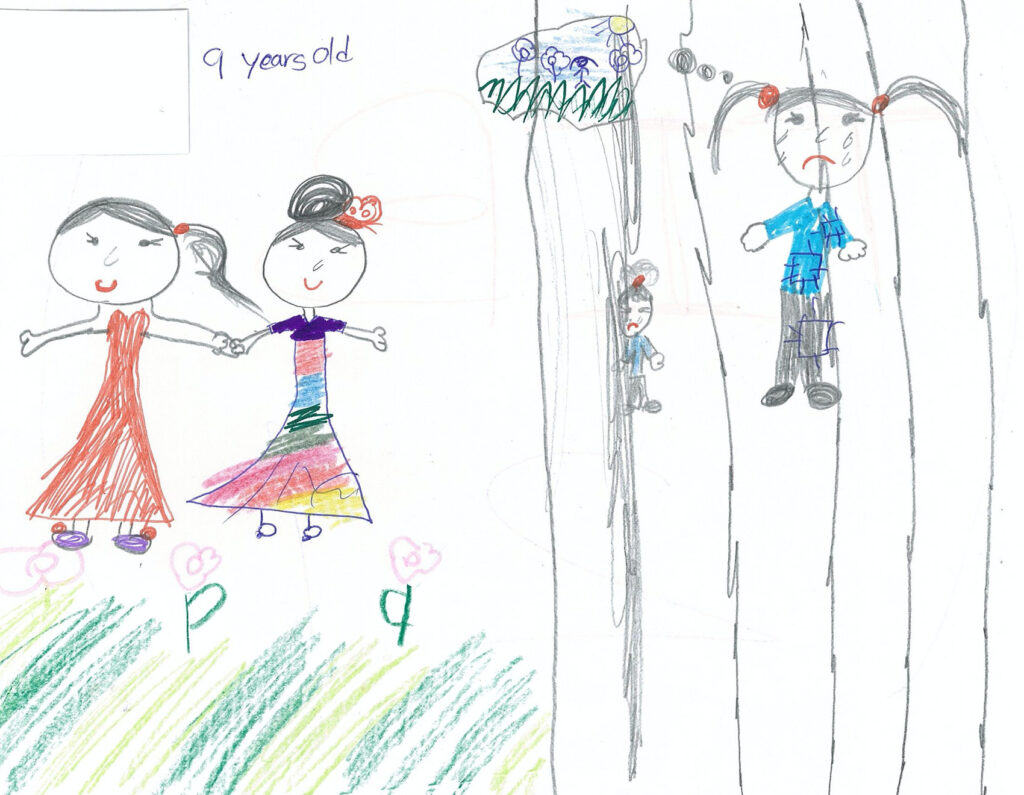

Deciding to embark as a family or send a child on a harrowing journey to the United States in the hope of a safer future must be an excruciatingly difficult decision.

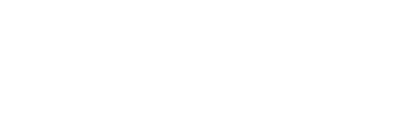

Arriving in the United States presents new and dangerous challenges, as detention centers are holding children for prolonged periods, under the premise that any non-parental guardian needs to be thoroughly vetted before being reunited with their child.

In the process, these centers may inflict immense trauma on minors. There have been various reports of minors being subjected to deplorable living conditions and even sexual abuse inside the detention centers.

Forced and Unnecessary Separation

Currently, because of a health order called Title 42, children who arrive in the United States with their parents are denied a chance to seek asylum and are instead returned to Mexico.

That order was scheduled to be revoked on May 23, 2022, but thousands of families have been expelled in the two years since the order was enacted.

Any children arriving in the United States with a family member who is not their parent, such as a grandmother who raised them, is separated from that family member and forced into a detention center for unaccompanied minors.

Family members must then go through a process that can take weeks or months to prove they are not engaged in human trafficking and then need to apply to have the child released into their custody.

Chief financial officer and co-founder of ESH Casey Revkin states,

“The government says it’s too much work to verify at the border that these family members are actually related to the child. That’s no excuse. It shouldn’t be too much work to avoid traumatizing a child.”

She adds that “An alternative [solution for determining a migrant child’s family relationships] would be potentially cheaper, too, because it costs between $200 to $800 a day to detain a child.”

Such solutions, Revkin suggests, could involve hiring social workers or investigators to work at the borders.

If you have concerns about a child’s treatment while in government custody, please contact ESH.

Moreover, you can sign up to volunteer for a specific team you feel most qualified to contribute to or, like myself, you can volunteer for different tasks across each team.

Whether it is thirty minutes to an hour of your day, any contribution is greatly appreciated.

You can find more information on how to donate, how to get involved as a volunteer, or how to sponsor a child at: www.eachstephome.org

You may also like

-

Vannessa Castellanos, la Estrella de Quoteasy

-

Lina Torres Trae a Broker Hub Realty Group: Su Mejor Aliado Para Invertir en Bienes Raíces en USA

-

Latinpro Insurance: Líder en seguros para la comunidad latina en EE. UU.

-

Fechas Límite para Radicar Planillas con Extensión: Corporaciones S, Individuos y Corporaciones C

-

Experience Kissimmee Lanza la Segunda Temporada de “The Kissimmee Experience”