Editor’s note: This post contains affiliate links. To learn more about our affiliate policy, click here.

Written by Samuel Olivo, Jr. & Tyler Fisher

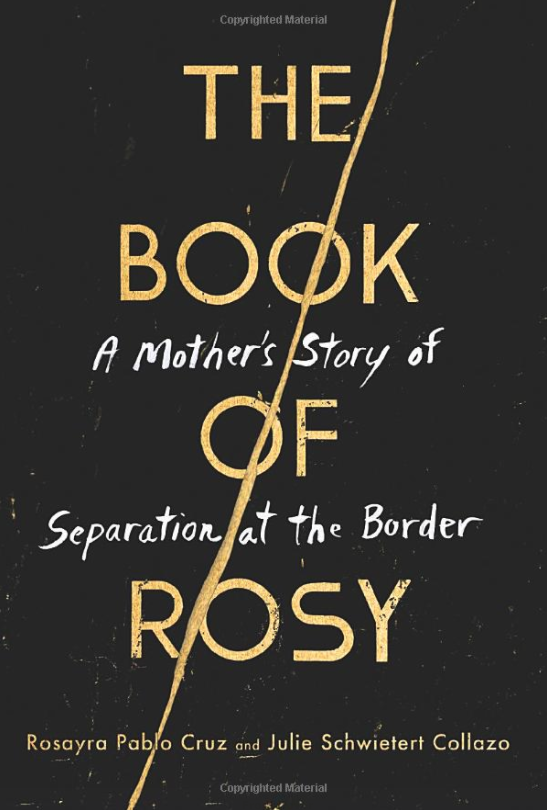

The Book of Rosy is a first-hand account of a Guatemalan mother and her children escaping violence in their home country to undertake a dangerous journey to the United States, alongside a first-hand account of the US citizens who rallied to assist them.

Rosy and her two sons endure separation at the US border under the notorious “zero-tolerance” policy, in force from April to June 2018. Rosy’s story is crucial for understanding the personal effects of this policy, alongside the broader contexts and backstories behind what the media dubbed the “migrant caravan” massing at the southern border.

This caravan of displaced populations comprises families trying to escape the harsh realities of their home countries for greater safety and freedom. Published simultaneously as El libro de Rosy: La historia de una madre separada de sus hijos en la frontera, this book offers an account that does not pretend to be the most heart-wrenching or gripping narrative of immigration, but it is a timely, richly representative record of human endurance and humanitarian intervention.

The Book of Rosy is organized in three different parts, each with a different perspective on Rosy’s experience. The first Part presents a first-person telling of Rosy’s life in Guatemala, beset by gang violence and corruption, which drive her to make the arduous journey to the US.

When the opportunity presents itself to escape, she leaves her homeland without a second glance, entrusting two daughters to the care of her extended family and taking two sons with her on the “Migrant Highway.”

Their journey culminates in detention and separation at the US border, where Rosy endures 81 days separated from her sons in “The Icebox,” the asylum seekers’ nickname for the austere Eloy Detention Center.

Ultimately, through the aid of the Immigrant Families Together (IFT) Foundation, Rosy reunites with her sons in New York City. As Rosy acknowledges, not everyone is as fortunate to be released on bond from the immigrant detention centers. Although the “zero-tolerance” policy has since been formally ended by executive order, many families remain detained and separated today, often in centers that can be veritable petri dishes for COVID-19 contagion.

In Part II, co-author Julie Schwietert Collazo recounts how she and her network of concerned working mothers founded the IFT from an initial “wild idea” to raise sufficient funds to reunite families separated at the border. Their efforts proved wildly successful, raising over $7,500 within their first day of social media campaigning.

ALSO WATCH:

As their resources grew, the IFT was able to reunite Rosy with her sons, as well as many other families. This part of the book provides unique insights on the other side of the story: the charitable, grassroots teamwork that brought Rosy’s family together again, with legal asylum, in their new home.

This part of the book may not be as riveting as the story of Rosy’s migration and detention, but it showcases a key piece of the current puzzle, foregrounding the personalities and voices that advocate for more humane immigration policies.

This focus continues in the book’s third Part, which interweaves both Rosy’s and Julie’s perspectives on how her life has changed since release from the immigrant detention facility and awaiting her asylum hearing.

At times, the alternating first-person accounts in this section may be confusing, but bringing these co-authors’ storytelling together for the book’s conclusion is an apt reflection of their collaborative efforts to raise awareness of a wider, more complex experience.

“In this book, I am both grateful and proud to help tell Rosy’s story,” Julie writes, “but also, to give her the bullhorn. Her story is just that—uniquely hers—but its basic contours represent the stories of thousands of Central Americans seeking refuge in the United States.”

It has been said that journalism is the first rough draft of history. Personal memoirs like The Book of Rosy can serve as the second draft, offering a more sustained, in-depth account of stories behind the headlines. Without books like these, those personal stories can too easily be overlooked or misconstrued.

As Rosy explains, “This is the immigrant experience I wish people could see, not because it is my experience, but because it’s the story of so many of us, coming to the United States to escape violence and to build lives in which we will contribute fully to society. We are grateful for any support, but we’re not waiting for a handout. We want to be part of your American dream. We want to help you realize it. We want to share in it with you.”

You may also like

-

CALENDAR OF EVENTS AUGUST – SEPTEMBER 2025

-

EDITORIAL Depende de ti tu horizonte

-

Puppets Equip Inmates to Practice Future Interview Skills at Osceola County Corrections

-

J Balvin Deslumbra en Orlando en su gira “Back to the Rayo”

-

Orange County Government Announces Events Celebrating Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month

1 thought on “Behind the Headlines on our Southern Border: A Review of The Book of Rosy”

Comments are closed.